Katie Steedly’s first-person piece [The Unspeakable Gift] is a riveting retelling of her participation in a National Institutes of Health study that aided her quest to come to grips with her life of living with a rare genetic disorder. Her writing is superb.

In recognition of receiving the Dateline Award for the Washingtonian Magazine essay, The Unspeakable Gift.

Enter your email here to receive Weekly Wide-Awake

Just Like Me: A Gratitude Conversation With Dr. Robert Roeser

KSC: For what are you grateful?

RR: There are an enormous amount of privileges that have been given to me in my life, both materially and spiritually. I guess those are the things I am most grateful for. This life that I have been granted. I am aware that it is a life of tremendous privilege in many ways.

KSC: Has the awareness of that always been there, or is it something that you came to at a particular time?

RR: You should know that I think gratitude is an important skill and disposition, but I don’t know if it is central to…I think humility. I think gratitude. I think awareness. I think they are all in sort of a curry together. To sort of single out a single phenomenon that’s oriented my spiritual life since I was young doesn’t ring true to me. For me, connecting deeply with people and seeing a sense of “just like me” has been the animating theme of my life. That is at the root of compassion You sort of understand other people have their own sufferings and their journey and you are not alone in both the joys and the sorrows of life. I think that awareness is a little more at the center of what my experience has been spiritually. Your cup runneth over, that you get to meet wisdom figures in any way, and go deeper and see beyond the surface of life. Living here in India it is just so palpably clear how lucky I feel for all that I have been given.

KSC: Is there a connection between gratitude and seeing other people?

RR: Maybe I can tell you how I think about gratitude in my own life, which is, not enough, is probably the simple answer. I can tell you how I think about it scientifically. The human mind, and I don’t mean your mind or my mind alone, but I mean the mind writ large, was really designed as a threat detection mechanism, and a pattern recognition system with the goal of keeping us alive. It inclines towards events that are threatening to our wellbeing or survival. This is called the negative bias. We have a mind that’s going to remember things that did not go right and that are troublesome to us. We are going to create a rich library of memories for those things, and the good that’s in our life. All the good that is here, whether it may be even just having a good place to be, or food, or no pain in one’s body, if that is the case. Whatever those good things are can be overlooked for those things that insult our sense of self, or bodily integrity, or whatever it is. From that vantage point on the spiritual path, one of our first steps, and I think this is why remembering the good and being grateful is often emphasized on the spiritual path, is, we have to train our minds to see a bit more fully and clearly what is actually here, because the mind is actually filtering out a lot of good things because it is tending to focus on the negative [for] survival.

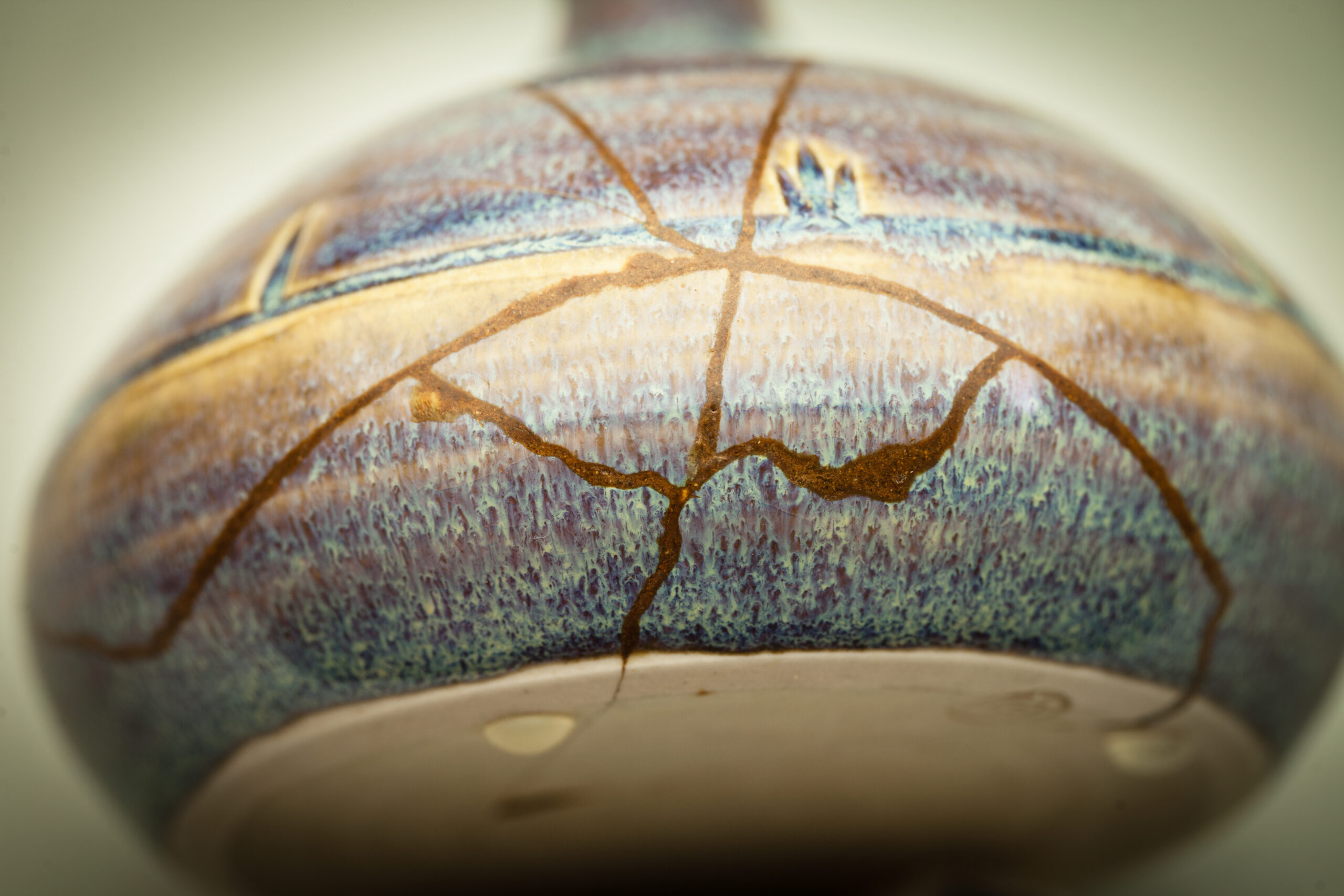

Someone once told me, if you have a steel pot and it has a crack in it, all the energy from the fire will focus on the weakness in the metal. I think our minds do work a bit like that. [They do] not notice all of the even places in the pot. [They focus] on the cracked area instead. In that sense, I think it [gratitude] is an important first step. I think that is why successful people, and people that are happy, their minds have inclined towards the good that is present alongside the difficult and the sorrowful, and probably what marks them as unique in our experience. They are a bit optimistic. They are a bit more glass is half full. Really. In a sense, the glass is both half full and half empty. That is what they are acknowledging, perhaps. Being able to see the fullness.

KSC: Could that perhaps be a survival mechanism? Not always focusing on that kind of “killed or be killed” [but instead] the capacity to be full.

RR: I think so. I think you are onto something here. This is the link with awareness and what the Dali Llama would say is, we have to see clearly what is here, and what is here is both suffering and joy. It is not one or the other. They are both here, and in fact they are related. Allowing our awareness to presence, to whatever phenomena is here, is one way to think about the development of our capacity to be mindfully aware. We can hold more and more and more of what is already here, and to that extent, the Dali Lama would say we are getting more realistic. We are coming into the presence more fully of reality, rather than this biased attention that can kind of screen out a lot of the good. On the other side, you have this sort of cotton candy idealism that wants to screen out the suffering and present that everything is roses and puppies and somewhere in the middle is the truth. Both are here. We need to be more realistic.

Gratitude is an element of it.

KSC: Gratitude is an element of the authentic.

RR: I think so, and to go further with what you were asking earlier, our whole life, and this goes on to the concept of interdependence. It is impossible not to be grateful for your life because so many people have made it possible. The people who cooked and arranged your food. Your parents who raised you. To not be grateful is also to miss something about reality, which is we inextricably rely on each other totally for our survival. To not acknowledge those people and parts and aspects of reality, the sun that gives light that allows food to grow and keep us warm and all of these things, is to sort of miss what is really here.

KSC: Is there a theory of change for mindfulness?

RR: I think, like anything, there are theories of change. Within the Buddhist tradition, there are many different views of what’s mindfulness. How is it cultivated? I think likewise, now the science on mindfulness. There are many different kinds of views. I want to talk about that, but I want to just go back because we were developing a theory of change around gratitude a minute ago, too.

To take your example of a cabernet. Let’s say that I do my gratitude practice at the end of the day. I say I was really happy to have that delicious glass of cabernet. On the one hand, we can see right away that you could have just had the cabernet and never acknowledged that it was something you were happy and grateful for. We already developed an awareness of that thing, the presence of that thing in our life. The first thing is just acknowledging the good. Right? Whatever theory of change we have, the first step is always going to be developing a bit more awareness of what is here. Then you may take that a few steps further. You may look down at the ruby red color of your glass of cabernet. If you have eyes to see it, you my thank the sommelier who suggested it for you. Then you might even be able to see a little bit further and be able to see the people who shipped that bottle of wine, or even the restaurateur who picked it and had it shipped. You might see the driver of the truck that brought that wine to you. If you go deeper, you might see the grapes in the field, and the farmers. You might see the immigrant workers who picked the grapes. You might see the rain and the soil and the sunlight that allowed all of those factors coming together to produce this varietal that you love. In some small sense, you could go from a simple awareness of something you are grateful for, to a deep, deep insight into all of the interdependent causes and conditions that allow you to enjoy that moment in your life.

Now your gratitude is moving in the direction of wisdom because you are starting to see something about the nature of your reality and your experience, which is interdependent with so many other beings. Now there is a gratitude for being part of this incredible flow of life, not just the sweet or delicious finish of that glass of wine, or the bouquet. It is something more than that you know. “To see the universe in a grain of sand and eternity in a moment,” as William Blake would say. I think there is something about awareness and then there is the development of insight and understanding into that which you have become aware of and that has different levels. I would say that is the simplest theory of change. We need to come into the presence of what is here and then to look deeply and try to understand what are the causes and conditions that brought about that experience.

KSC: Why the “why” matters. The moment when the “why” matters.

RR: Even the “what.” What caused the cabernet? The “why” is a little mysterious, like why did the sun, rain, and soil produce it? That can be important too. That is a part of understanding: there is some chemistry. It could be otherwise, and all grapes could be bitter. I think you are right, but there are just layers and layers of insight that is possible, but only with awareness first.

KSC: When Camus writes about wide-awakeness, he writes that wide-awakeness starts the minute the “why” matters, we are moving from the rudimentary mechanical movements of life to the something else.

RR: Exactly. I think that is right on. We take for granted so much. We need to inquire into why is this the way it is. This is so true. We take a lot for granted and suffer a lot.

KSC: It is interesting that in the taking for granted, in our silence and in our fog, we suffer more. You would think it might be the opposite. The less we are aware of. A kind of ignorant bliss. Our ability to feel and empathize and connect is both a gift and it hurts sometimes, too.

KSC: As someone who has been on a spiritual path and has tied that path to an academic journey what have been some of your most interesting findings?

RR: I want to preface this by saying one of the things, other than my family and all of the people in my life, that I am most grateful for is that you and I were born into a time when ancient wisdom and modern science have come together in a way that does not distort either of them and is trying to create new understandings and new kinds of human services that help more and more people. Despite all the other mischief going on in the world, there are a lot of amazing opportunities in this life that we have been born in to.

Let’s take one of the key insights that I think has come out of this work. It is something that I did not have a name for because it is before language. It is the importance of the body and sensation and feeling, to wisdom and ethics and the path to a good life. The body and the sensory experience and our feelings really are our guides in this world. Psychology and philosophy in the Enlightenment era when Rene Descartes sort of elevated cognition and then science in the twentieth century focusing on thought and rationality. I think all of that is critically important, but it needs to be married to rather than seen as the antidote to overcoming our feelings and sensations. I think the integration of all these different ways of knowing through the senses, through our feelings, and through our rational and analytic capacities is in some sense what it means to be whole. It is bringing in all of those aspects of who we are and ways of knowing ourselves and other people and the world.

I think that the body matters. Coming to our senses is really important. That feeling is first. “That who pays attention first to the syntax of things will never wholly kiss you,” as ee cummings put it. Like shut up, stop talking, and just kiss me. There is an important insight in there. That there is a way of knowing that is very important. This is before language. That is not to say language is not absolutely important and essential to being human. It is really marrying these things together which creates what is quintessentially human. So often in mindfulness practices or gratitude, we remember experiences we are grateful for, and the first thing we say is not “Why are you grateful for that,” which is an analysis and can be very important, but we might just say “What does that feel like in the body, as you have that memory.” That is the whole sense memory and learning from our senses.

KS: Is there a cultural component to gratitude?

RR: I think it is there. It is always there. I think it is critically important to acknowledge. The first thing to acknowledge is there is no way that these practices travel to different places and lands and don’t get refashioned in the direction of the local norms. For instance, yoga being turned in to sort of a commodity that is about a beautiful body in America.

I was listening to Dalai Lama the other day about the different religions of the world. He said a couple things. He said there are three levels. The first is that there is this common goal which is more love, more kindness, more compassion. This goal is really at the center of diverse cultural religious traditions. That is common. He said the second level is philosophy. There is a lot of difference in how to realize greater love, greater gratitude, greater kindness, and there is no problem. He said there are many different paths to the same outcome. Many different trains arrive at Grand Central Station. No problem there. Then he said the third level is the cultural level. He was referring in this case to the caste system, but he could have been talking about race relations in the United States. There is some need to really be critical and thoughtful and really examine how these things, how do the cultural ritual and norms and values match this deep, deep goal. In America, everything will always be filtered through an individualistic frame. Immediately. We will see mindfulness as a self-help technique which you know this is not the understanding of some of the Asiatic traditions. It is about coming into a sense of communion and interdependence. I think we always want to be aware that there are cultural factors that are going to interact with these wisdom factors to produce different manifestations, some of which are beautiful and new, and some of which are potentially obfuscated or appropriated in ways that really take us away from the power of these practices.

What we have been trying to do in contemplative science, the only corrective to try and work with that, is to have diverse points of view in working groups who can dialogue across the boundaries of culture and context and time to try and manage that complexity.

KSC: How does one do that? Does it start with children? Can adults do that? What does it really look like?

RR: For instance, if we are creating a program for mindfulness in schools, it may be useful to have a working group. I will give you an example from some of the compassion training practices I have been involved in where there is an emphasis on “Just like me,” as a basis for compassion. There is a lot of beauty and wisdom in that, and yet if you are working with communities that have been traditionally oppressed or where massive violence has been rained upon them by dominant groups, you may need to really think about it. Is that framing emphasizing “Just like me” the only framing that is going to speak to oppressed or marginalized groups? Does there have to be an acknowledgment of that suffering and the like? We have to try and create diverse communities to create these kinds of programs and practices because we are all going to come from our own positions and the biases associated with those positions. The only way through this thicket is through dialogue and intercultural exchanges, and that can happen within a country, or within Texas, or within wherever it is. There is diversity in every place

KSC: What is the roll in reaching out to cultivating gratitude? I think it goes back to what you said, that a piece of that for you is being connected. When you go to develop or work with a new group, how do you initiate those relationships? How do you set it up to head down a path of interdependence?

RR: As practitioners, we are always called to be humble and self-aware in the knowledge that if we think we have the answers, we are in trouble. All of us think that. No matter what we do, we are coming from a specific position and perspective. I think we have to use that awareness. What I should be doing is really listening and reaching out to disparate communities with whom I want to do this work, and really start to think about a collaborative model. In contemplative science, we would want a practitioner who has expertise in wisdom. You might want to have a scientist who has expertise in the science. You might want to have an educator who has expertise in pedagogy. Then you might want to think, “Who is not in the room?” “Why are all these white people here?” “Where are all the ethnic minority people?” We have really started to think about how to marry issues of equity with issues of contemplation and compassion, because this movement is rolling out as somewhat of a middle class, white, European American movement, and how do we work on that issue and challenge?

KSC: Making a deliberate effort to create a space at the table is a good place to start?

RR: The issue we are talking about here is you want to balance a focus on commonality and common humanity. In this work, gratitude is good for everyone, an appreciation of diversity and equity that different people are going to come at this through different pathways from different historical experiences, and we just want to be mindful of our experience and expectations and assumptions. They are situated within a particular context. How do we make sure we can make some space for other kinds of insights and approaches and voices right from the very beginning, not just as an add-on, as a module that comes later, but really, right at the outset as we are creating a program or a study? How do we design that in with the intention that the program or study has maximal impact because it has been designed well for a diverse end user? I think this is the challenge in the next phase of the work. To become more inclusive and really attend the issues of equity and diversity in our working groups in our programs and then in our program evaluations.

KSC: How do we take that critical perspective and allow that to inform, as the Dali Lama suggests, love, philosophy, and culture? How do we allow the science to inform our understanding that in our difference there is still commonality?

RR: Exactly, I don’t think there is any way around it other than having diverse working groups. I mean everyone gets culture, so we are not going to get outside of culture. What we are trying to get beyond is a monocultural working group so that we really bring in diversity.

KSC: That is rooted in the existential thought that you are both in an experience and of an experience.

RR: Your own journey with Maxine Green. You are already there with that critique of structural inequality. At the heart of that is a desire for love and equity and fairness and justice. There is nothing incompatible about these things, but the way that they get constructed sometimes.

KS: The critical role of the imagination. The critical role of being able to imagine. If we want peace we have to be able to imagine peace, create that in ourselves and in our relationships daily, and work towards that from the inside out.=

RR: I just want to say something about the role of imagination. We do compassion practices. You may be asked to imagine extending love and kindness to all beings. If you think about that for just a minute, that is a very abstract idea. It takes an enormous amount of imagination to wish the caterpillars, and the birds, and the four-leggeds, and the swimmies, and winged ones, and the humans. All of them are deserving of love and kindness, and don’t want to suffer. I think there is something very beautiful in the human capacity for imagining a reality that isn’t necessarily present here at this moment in our awareness.

KS: Wide-awakeness is about being awake to what you want to create. Releasing your imagination to think. To have the audacity to say peace is possible. We can eliminate hunger. What does that look like? What does it really look like to have a world where no one is hungry? Where everyone has enough food? Where disease is gone? How do we move towards a world of peace? If we are connected. If you believe in interdependence. The implication then becomes that if that person does not live in a peaceful community, then I don’t live in a peaceful community. What does that mean if those children are hungry? Once you believe in interdependence you can’t get off the hook.

RR: Reason and imagination are keys. Empathy. Emotions. Feelings. Reason. Thinking about the other. We have waste. That is not fair. Then imagining. Like we were talking about the cabernet. It takes an act of analysis and imagination to see all the beings and factors and conditions that produce that delicious glass of wine. I think cultivating all the capacities that are already with us is the way.

KS: Is there a piece of your work that bubbles up as really valuable?

RR: How to study the spiritual or the inward development of a person? The answer in the scientific community has to do with the integration of different ways of knowing. We think about those. There kind of vantage points that we want to attend to. One is the first-person experience. What is the person’s experience phenomenologically of their own development? We really want to listen to the voices and gain the insights of the people we work with because their intimate, subjective, first-person perspective is very important. Now, at the same time in science, we don’t want to just privilege what people tell us because sometimes we are prone to self-illusion. Then we also want to have a third-person measure. Wouldn’t it be beautiful if I could give you a measure that really looks at how long you can attend and sustain your attention on a single object and measure that objectively from a third-person vantage point, and marry that with your own perception? You know what I mean. At the dinner table with my partner, I am really able to focus on what they are saying and listen better. If we have those two pieces of data. If we have the person saying “This is what is true for me,” and then another scientist saying, “Well, we measured that in this person. Indeed, they seem to be better at this skill, on this measure that we have now.” We would have a little more confidence that their attention has improved. Then there is a second-person point of view. We could just ask their partner, “Do you feel like your partner is a bit more attentive now because we have an expert reporting on you, a second person view?” You say it’s true. Your partner says it’s true. The scientific measurement third-person says it’s true. Now we are triangulating. We are getting much more confident now that something is really happening here. If just your partner says it, I am not sure he or she could be biased. If just you say it, I am not sure he or she could be biased. If just the measure shows, okay, but measures can be reliable or valid or not. If we start to knit those different ways of knowing together, now we are moving in the direction of greater confidence in our truth claims. This is the way the science has been evolving: really not privileging the first person, or the third person, or the second person, but trying again to coordinate them and bring them into relationship with each other

KSC: How have you studied that?

RR: In our studying of teachers, we ask the teachers how they feel before and after training. We interrogate their saliva for stress hormones before and after training. Then we ask their students to report on whether you feel your teacher is more or less stressed after training. We have the first-person teacher report. We would have the second-person student report, as presumably they could tell us something about their teacher. Then we would have salivary cortisol levels. This is very hard to do. There is no doubt about it. The aspiration is to really try to tap into different ways of what is happening, hear different perspectives. We would say, “What have you learned about reducing stress in teachers? What are some things have you seen successful ways to do that?” I think over the last ten years, my colleagues, and my friends, and I, we have definitely developed an evidence base that suggests that mindfulness and compassion training can really be helpful for teachers. I think there is evidence that it can be helpful for anyone that works with that most stressful of phenomena called the human being.

The long and short of it is that we are starting to get some sense that these kinds of skills and dispositions that we are talking about: focused attention, gratitude, kindness, humility, we see them as skills can be cultivated through training. Then they can have utility value with respect to managing stress, interpersonal relationships, and physical health. I think the data is preliminary. I think we have a lot more to know, but I think we have some promising signs that these kinds of trainings that cultivate these kinds of qualities can help people to be happier and reduce their suffering levels.

KSC: How do you talk about that with school administrators and others within the educational landscape? How do you talk about that with people who say, “Well what does it mean for test scores?”

RR: I think you have to meet people where they are, and also be realistic. I think child outcomes and test scores are one way to think about education, but health care, cost retention, and training costs, there are different doors in. Again, I would say you have to do a lot of listening and trying to understand where people are, and think about if what you are doing realistically may or may not be of value. I don’t think we should be in the business of selling these things. I think we should be in the business of really trying to help people who have significant challenges, to solve those problems. Sometimes these tools will be helpful and sometimes more money for free lunches is a better strategy, or getting the lead out of the pipes in the schools is where the money should go, not to mindfulness training. I think we have to be realistic and humble and open in whatever setting we find ourselves in. There is no doubt that stress is there in these professions, so it is not a hard sell. Every administrator I talk to wants this for themselves because they are overwhelmed. You just have to find the course and that is called skillful means to help people think about how this may help them with love and kindness. We do that. Always bringing it back to the humble and to the humility of the real purpose: reducing the suffering, and helping the children and the teachers ultimately kind of create better worlds.

Robert W. Roeser PhD, MSW is currently the Bennett Pierce Professor of Care, Compassion and Human Development at in the College of Health and Human Development at Penn State University. He has a PhD from the Combined Program in Education and Psychology at the University of Michigan (1996), and holds master’s degrees in religion and psychology, developmental psychology, and clinical social work.

In 2005 and 2016 he was awarded a United States Fulbright Scholarship in India; from 1999-2004 he was a William T. Grant Faculty Scholar; and from 2006 to 2010 served as the Senior Program Coordinator for the Mind and Life Institute (Boulder, CO). He also served on the working group that designed the original Call to Care Curriculum for the Mind and Life Institute (Amherst, MA). He is currently serving on the planning committee for Mind and Life Institute’s 2016 International Symposium on Contemplative Studies.

Dr. Roeser’s scholarship and research is focused on schools as key cultural contexts of human development, and the use of contemplative practices in educational settings for school administrators and leaders, teachers and staff, and students. His laboratory is devoted to the study of the effects of mindfulness and compassion in education with regard to improving health and wellbeing, teaching and learning, and an equitable and compassion culture in education.

About Katie

From Louisville. Live in Atlanta. Curious by nature. Researcher by education. Writer by practice. Grateful heart by desire.

Buy the Book!

The Stage Is On Fire, a memoir about hope and change, reasons for voyaging, and dreams burning down can be purchased on Amazon.