Katie Steedly’s first-person piece [The Unspeakable Gift] is a riveting retelling of her participation in a National Institutes of Health study that aided her quest to come to grips with her life of living with a rare genetic disorder. Her writing is superb.

In recognition of receiving the Dateline Award for the Washingtonian Magazine essay, The Unspeakable Gift.

Enter your email here to receive Weekly Wide-Awake

What A Beautiful World: A Gratitude Conversation with Dr. Mary Lee Webeck

KSC: What are you grateful for?

MLW: It is important to say that I am not a religious person. I am a spiritual person. I think that drives how I think about what I am grateful for. I have always believed in my work with children, that helping children learn to observe the world around them is just utterly important. It is part of my personal philosophy that you can talk to children about the most devastating things human beings have done to each other if you also share with them, not in the same moment but in other moments, what wonderful things people have done, the beauty of the world. When you are an educator who is teaching about essential human behavior, it is really important to have that continuum of conversation that makes your framework.

A lot of the things that I am going to tell you I am grateful for are going to seem kind of weird. A couple of them come from observation. One of the things I am grateful for is heart-shaped rocks. This came from my learning and growing up around the Great Lakes and collecting rocks and beginning to find rocks that have been worn down by water into the shape of hearts. When I was a teacher in Indiana, we were able to take our fourth and fifth grade students to Lake Michigan for a four-day camping experience two different times. One of the things we taught the kids while we were there was to look carefully around the world and do journaling and drawing. It always helped them learn to find heart-shaped rocks. Now, I get heart-shaped rocks from all over the world from kids that were students. Then same thing looking out the window at a snowdrift and learning to think about and be able to describe that. I am very grateful for the human ability to observe, and to articulate, to learn.

I also always wanted to be a singer when I was a kid, and grew up with that television show The Flying Nun (which ran from 1967–1970). Sally Field was a nun. She just had such a beautiful voice. I just always wanted to be that singer. Today, I am still enamored by what the human voice in the singing form can do. This past weekend, I was on my computer and I tumbled onto a couple of people singing, and I was just…I don’t know, it just takes me away. Then there is Queen Anne’s lace, which I love because I grew up in the northern part of the country where Queen Anne’s lace grows freely in the wild. It always has, for me, been a part of just beautiful days, and outdoorness, and freedom, and I love it. I have friends who live in the north now — in Texas there is no Queen Anne’s lace — who send me photos they take of Queen Anne’s lace. I am into simple things, not shiny fancy things, that happen around and make me happy, and those things are all tied to memories and challenges that have been in my life and that have been important to me. There is so much to be grateful for . . .

I am also very grateful for the people who I have come to know in my life. There is a Holocaust survivor who is the reason I ended up in Houston. The reason I left the university and came here. I kind of fell in love with this woman when I first got to know her. I came to the museum, and was doing some work down here. I would go back to Austin, [and] for like the first year and a-half [that] I knew her, every night at about ten o’clock, my phone would ring in Austin. It would be her. Holocaust survivors, often if they have very horrific things in their memories that they have not talked about, they have a really hard time talking to their children about them. They don’t want their children to know that they suffered or to think about the decisions that they made that their children may or may not agree with. She was talking to me at ten at night. It started out in light conversation and would go into darkness and would, over the course of time, turn back to lightness. I just became very close to her, and she has been one of my best friends for the past ten years. She died this fall, which was sad, but you know she was ninety-six, and she had had an amazing life, so that was a good thing. She became very wealthy and was a major donor to our museum. Her children started a fellowship program for her which is the reason that I came from UT down to the museum. Sherry Field and I have been doing this now for fourteen years. It is called the Warren Fellowship for Future Teachers. Her family has done this. She would always say to the students. “Big changes, the kind that human beings need to make, begin with small changes.” I thought, “Oh. That is really because big things, you can’t just do them. You have to work up to doing them. They have to become a natural part of you.”

I am grateful for my children who have taught me so much about humbleness and challenges that people face and what makes people individual.

I work at a place with 110 volunteers and they all have their individual needs; they need to be stroked in different ways. They bring different wonderful things and challenges with them to their work here. I am just so thankful for what they teach me again about humbleness, and again about what people can do and what happens to people. You know life is tough and that is enacted around us every day. Those are just a few things I find important.

KSC: Do you have a gratitude practice?

MLW: I try every day when I get up, in my head, to make a list of things I am grateful for. I try to start with whatever is most challenging to me at that moment. For example, this morning when I woke up, I had had a really difficult evening last evening. I got up. I thought, “It is going to be an interesting day today, so why should I be thankful? That I had to get up and go to work? Well, first I have a job in the economic uncertainty that is right now. I need to be grateful that I have a chance to go to work today and do a good thing.” That might not be how I am feeling. Mostly, I would just say I try to think. I don’t, unfortunately, write [in] a journal. I don’t do that anymore. I don’t exactly know why. I guess laziness, honestly, more than anything.

KSC: Is it easier to connect with gratitude on certain days?

MLW: There are easier and harder times. I think that gratitude is felt on so many levels, your emotional capacity, and whatever time in your life you are dealing with, changes. For example, I have a friend and she is no longer living. She was an outreach coordinator for the Houston Grand Opera. An amazing talented theater worker, musician, and educator. Her capacity to give of herself, and her capacity to draw out in people around her what they were great at was such an enormous gift. She died last year and I got to spend a fair amount of time with her toward the end of her life when she was in hospice. This is going to sound really weird, but there were forty-five minutes that I spent with her a couple of days before she died. She was asleep while I was sitting there, and the nurse came in and said, “Well, she is asleep,” and I said, “Well, I know, I just want to be with her.” It was just like this beautiful thing that I will forever be grateful for and feel gratitude. I was welcomed into that space even though she did not consciously welcome me into that space. I welcomed myself.

KSC: I know exactly what you are talking about.

MLW: That feeling. It was so special and I have never felt that before with anyone or for anyone. I am so thankful that I was able to have that experience. To know that there is peace, and that you can share that with someone else.

KSC: When I think about moving from what are we grateful for, to how do we practice it, to can we learn it: In your work with young people, when you talk about those moments, do you think we can learn these things?

MLW: I think we can. I think that because everybody would approach it differently, there is a teaching exercise that I do sometimes with the Warren Fellows who are all preparing to be teachers. I tell them about my belief that you can teach children about the most horrendous things that have happened as long as you balance that with teaching them about beauty. There are two books that I read them. One of them is called A Prayer for the Twenty-first Centuryby an Australian young adult novelist, John Marsden. It is a poem that was written right before the year 2000. It is a prophetic poem. It is really powerful. It is about darkness. It says knowing the names of the things you fear — and for kids I know that being able to put a concept or a name to something — is so important when they are trying to deal with trauma or things they are afraid of. Can you put the gun back in the holster? This is weird. This was before September eleventh. In this book, [when] a person [is] flying in an airplane, many destinations can be safely reached. When you read it after September eleventh, it has a different meaning. Actually, a picture of a kid jumping off a haystack and talking about, “May we work through the things we fear.” It is a very introspective book. It is kind of a dark book. It is one that the students really, really, really like, for the way it asks them to consider difference and challenges.

KSC: How long is it?

MLW: It is short. It is a poem. About twenty lines.

Then after that, I play Louis Armstrong, “What A Beautiful World,” and show them the picture book, called What a Wonderful World, that’s illustrated by Ashley Bryan, who is an African American painter who does really very simple beautiful colorful things. It is just a really nice continuum of how do you help people think about the worst things people have done and the most beautiful things that are in the world. Concrete examples of that. I have had a lot of those teachers write me back and say I used those two books with their students.

I currently teach a class at the University of Houston, “Us and Them: Decision Making in Complex Cultures.” It is an undergraduate class in the Cultural Studies Department which several students studying Anthropology take. I love anthropology and the kinds of thinking it encourages. I should have been an anthropologist. That class has been an interesting experience. I have had profound reactions to it because I don’t have a really set syllabus. I say to them on the first day of class, “So tell me something you are concerned about in the world.” It is deadly silent, so I start to tell them, “So here’s a few things that I have been reading this week. Then I assign them to bring in three news events from around the world. Two of them have to be [from] an international news source. One can be an American news source. Second week, it is still pretty quiet. By the third week, they have started to just blow the top off of the world for each class I got a letter from one of the women who is living in Guam now. She sent it the morning after the Paris terrorist attack. “I just wanted to tell you it has been two years since I was in your class and I think about your class almost every day. I want you to know that, because you changed the person that I am. Now I think about people around me.”

KSC: Is there a more important thing?

MLW: It has been really cool. I am hoping to teach it again in the fall.

KSC: How big was the class?

MLW: The first two times I taught it, somebody paid for it. It was tiny. Seven students. The second time it was fourteen students, which was great. Sometimes you need a small setting for the kinds of things we were doing. That is something that has made me feel a lot of gratitude.

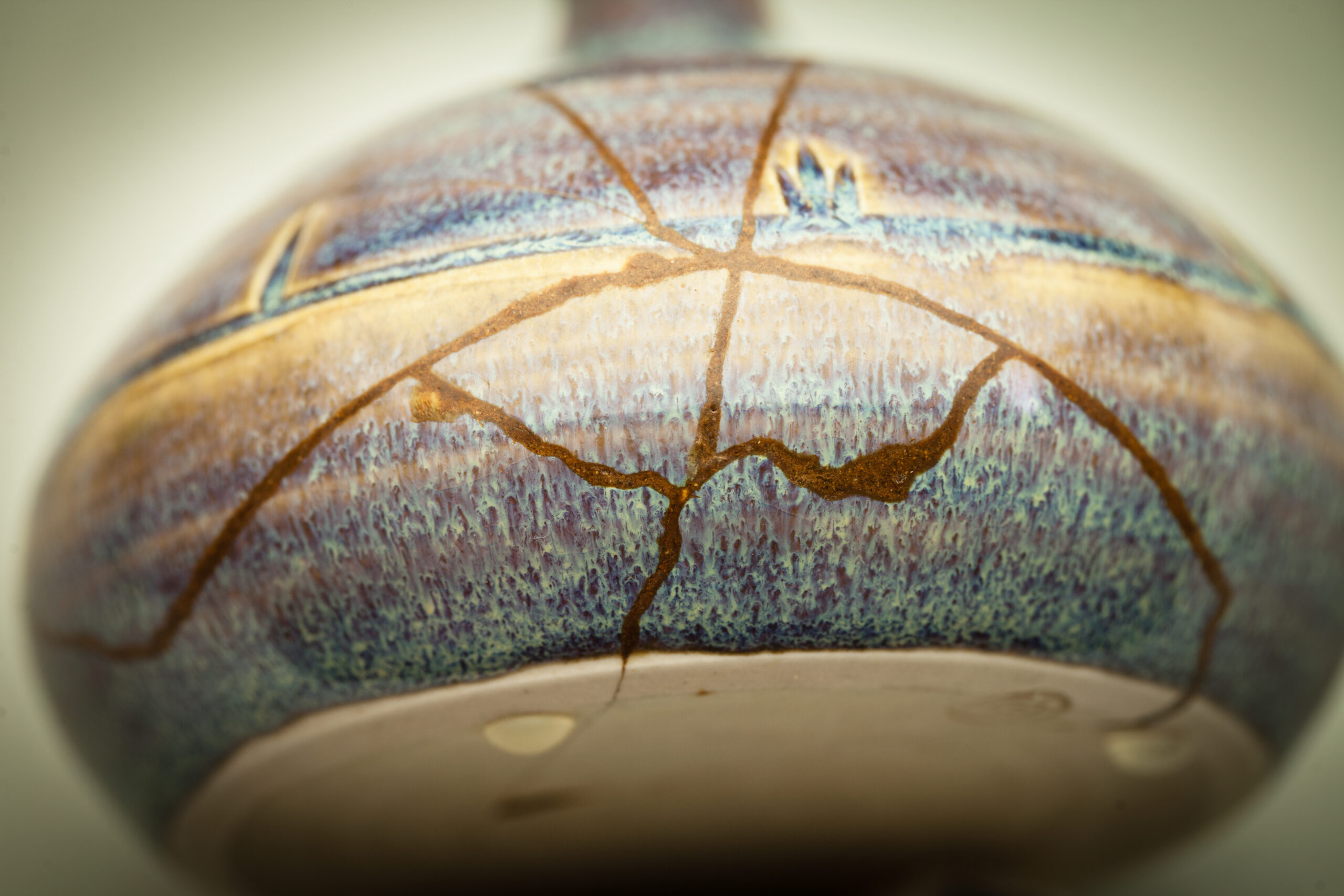

Mostly I feel gratitude, rather than practice it. I have always said, “Learner teacher, and teacher learner,” and I think these two things are so commingled that you can’t practice it unless you know it on the continuum. Like on the poem I sent you [by Naomi Shihab Nye, called “Kindness”], before you know what kindness really is, you must lose things, or before you learn the tender gravity of kindness you must travel where the Indian in a white poncho lies dead on the side of the road. There is one more that is really good. Before you know kindness as the deepest thing inside, you must know sorrow as the other deepest thing. I am always about opposites and reflecting on what there is in between. What there is at both ends, and what there is in between and all around that fullness. A way into talking about darkness, and the darkness of moments, and the darkness of the human spirit.

I always think about, “What are the entry points that you can use with people to begin to have really deep conversations.” That’s part of my work. Thinking about how to do that. To begin to do that. How to draw people in. How to keep them safe while they are there. Some people say, and I don’t necessarily like this, and I am not necessarily sure why, but they say, “When you are doing holocaust education you have to take them safely in and then take them safely out.” That is sort of what I am trying to say to you: there is something that is lacking in that for me because I know that there is a level of horribleness and darkness that you have to go through.

KSC: How much do people need to know? How much do people need to agree? How do we talk about difficult things?

MW: How do you teach people about genocide?

KSC: Without othering and making, “Well that was then, or it did not happen,” or all of the crazy thinking that surrounds how folks can’t realize how that was in the human capacity and would rather believe lies than really say human beings were capable of.

MLW: I have always said that when you teach a child about the holocaust you teach them about the darkest possibilities that there are and that changes their world. I believe that pretty severely, to loop back around to gratitude, once your eyes are open, once you have that understanding. How do you see the fullness of the human spirit ever again? There is a statistic from the Holocaust that is so compelling to me. We know that less than one tenth of one percent of people acted in the role of helper during the holocaust for very, very, very good contextual reasons. For threats to themselves and their families. For me, though, the fascinating question is what makes the one tenth of one percent unique? That statistic breaks down, and we use it very effectively. Like, say we are talking to a whole school, and there are 3,000 kids in the school. We are talking to the senior class and we say, “So what percentage of people rescued others during the Holocaust?” They say seventy percent, [and] some as low as thirty percent. Then we tell them the real statistic and say, so given the population of your high school, 3,000 students, how many statistical rescuers could we make out of this population? The answer is three out of 3,000. That is a stunning thing to think about. There are things that are known about people who were rescuers. They don’t follow the rules. They do what they think is right. They don’t recognize boundaries. They do what they have seen done around them. It is very fascinating.

What we know about the education system is, it is all about rules. Sherry and I had our preservice elementary social studies teachers administer a survey, and we got 5,000 results from kids. Terrifyingly, doing well on the test, following directions, and doing what you are told are most important to kids. I said to Sherry, “There is not one activist — one or two kids — [that] said ‘I would stand up against what is going wrong around me.’” It is a fascinating thing. They felt like that was what they were supposed to say.

KSC: Is there a relationship between obligation and gratitude?

MLW: I would say there is, usually. I am just thinking about the kids I talked to yesterday. One of my questions to them was, “What is it that makes you feel obligated to that person?” Some of the responses were, “They help me.” “I am thankful for my grandma who takes care of me.” These were like kids who are living in tough, really tough, tough, tough places, you know. Probably many of them living with their grandmas because their parents are adjudicated or not around or whatever. I think there is a strong sense of gratitude that is involved in obligation. I think that is a part of it, but I think you are talking about, why be obligated?

KSC: I am curious about a depth of understanding beyond a quid pro quo: “They give me this so I am grateful.” A kind of transactional gratitude. Is there is something deeper?

MLW: For me, gratitude is a sense of being. It is a perspective you take toward the world. People that live with gratitude for the world, for the things they have, for things they care about and others, do not have a sense of entitlement. They are people that are usually trying to work something out. Trying to figure out what gratitude means to them, even if they have never asked themselves “What does gratitude mean to me?” It is a part of their daily existence. It is a way of being.

No, I think what you are getting at is, there is a presence to those people, that, and an awareness that is ultimately a question: “What are the blessings in my life, [and] what am I doing today to be part of the world.

About Katie

From Louisville. Live in Atlanta. Curious by nature. Researcher by education. Writer by practice. Grateful heart by desire.

Buy the Book!

The Stage Is On Fire, a memoir about hope and change, reasons for voyaging, and dreams burning down can be purchased on Amazon.