Katie Steedly’s first-person piece [The Unspeakable Gift] is a riveting retelling of her participation in a National Institutes of Health study that aided her quest to come to grips with her life of living with a rare genetic disorder. Her writing is superb.

In recognition of receiving the Dateline Award for the Washingtonian Magazine essay, The Unspeakable Gift.

Enter your email here to receive Weekly Wide-Awake

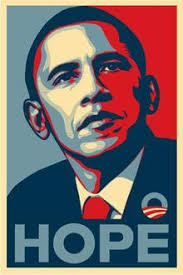

Hope and Change: What I learned campaigning for Barack Obama in 2008

Change will not come if we wait for some other person or some other time. We are the ones we’ve been waiting for. We are the change that we seek.

Barack Obama

Making My Way

I drove off at 7:01 a.m., just as the parking officer was about to ticket my car. I took Lucy, my Himalayan cat of fourteen years, and hit the road, leaving Washington, DC, in my rearview mirror. By luck and/or design, my nine-to-five job (like so many other people in 2008) had ended the Friday before and I was off to volunteer with the Obama campaign in Indiana, the state in which I grew up. This was the first time since Lyndon Johnson was in office that Indiana might “go blue” in a presidential election and I wanted to be a part of this tectonic shift in a place to which I am undeniably connected.

I was not going to knock on doors and make calls in some random locale — even if that other place was also “in play.” I pledged to myself years earlier never to watch election-night returns thinking I could/should have done something. No matter what the result, I would be able to look at myself in the mirror and feel like I did my part, and I wanted to do my part at home. I wanted to be able to say to the people with whom I grew up that voting makes a difference and our world depends on everyone being heard. I wanted to be a part of supporting what I believe to be the better political angels — healthcare as a basic right, human rights in general, respect for the earth, and the basic premise that effective government, not corporations, must guide society.

My work had taken me away from home for many years, but this work took me directly back to the roads on which I learned to drive. Voting happened in the very schools I had attended. I had lived all around the country and wanted to be home. The Campaign for Change was part occasion, part excuse, part fuel to the fire to connect with my roots.

The Work

I drove directly to the converted theater in downtown Jeffersonville, the town in which I grew up that was serving as the local field office, seeking an assignment for the very next day. While I was still in DC, I had been in contact with Nate, the field director who headed the Clark County campaign office. He was a Political Science major who had graduated from college and gone to work on the Obama campaign in Iowa, well over a year before this presidential push. With blue jeans and shaggy hair, he looked more like he belonged in an Austin coffee shop than on the political path heading to Washington. I walked into the field office and introduced myself. Nate was pleased to see me and let me know everyone would be registering voters on the campus of Indiana University the next day. I had graduated from IU (quite a few years before), so heading back there on my second day was a natural fit.

Indiana University

Standing at a bus stop outside of the IU student union, my father (who was also an IU graduate, who had traveled with me to register voters) and I asked all passersby if they were registered to vote. One after the other, they saw the stickers on the backs of our clipboards that read, “5 Days Left.” They would either respond with a thumbs-up, pretend we were not there, say they had already registered, or profess their support for McCain. The vast majority of passersby were students who were already registered. Judging by their friendly natures and supportive glances, I think they were also overwhelmingly Obama supporters.

Walking back to the Bloomington campaign office we ran into a group of late-teens on skateboards in front of the library. They saw us carrying the clipboards we had used to register people. I asked them if they wanted to register. The only young woman in the group spoke up from behind her jet-black and turquoise bangs. She said, “I don’t vote. If I did, I would vote for McCain.” I asked her why and she explained, “He is older. I trust him. And anyway, they all lie in the end.” Her boyfriend chimed in, “They are all bought by corporations, so it does not matter.” I then tried to explain that I believed there was a distinct difference between the candidates and that not voting does not make the situation any better. They defended their position and their right to remove themselves from the system. As I stood there, I wondered if their objections were based on a contrarian impulse in which they saw momentum building around one candidate and thus their response could only be to oppose the groupthink. How could they be both young and so deeply cynical? I did not think they knew something I did not know. I certainly believed there was a difference in the candidates. I quickly realized that my words were making no impact. Their heels were dug in, so my father and I walked on.

Knocking on Doors

My next few days were spent knocking on doors in public housing complexes and neighborhoods of varying descriptions. I went equipped with registration forms and pens to make sure that I could register people or provide absentee ballot applications. As I went door to door, I talked with people who were truly the most vulnerable to the policies that would be decided by the elected officials. I canvassed public housing projects that provide roofs for families of all descriptions and senior centers where fixed incomes dictate meals and medical treatments. I talked with people who spoke English and people who did not. I talked with people who had never registered to vote, much less voted. I talked with veterans who struggled to get benefits from the Veterans Administration. I talked with convicts who had served their time and could vote in Indiana but had heard they could not.

The neighborhoods I canvassed, for the most part, had seen better times since the days when I visited grade school friends and played on the swings in their once-new playgrounds. There was a sense of being forgotten. I see voting as a way for the people who lived there to say, “We are here, and we matter.” I identified with them very deeply. I drove around town (despite being told that I should not be in some of these places after dark) with my clipboard, forms, and pens in hand. I could not understand how neighborhoods had become so violent that it was not safe to encourage participation in the political process.

This was the first time in my life that this area had been worth the political capital expended in large-scale political campaigns. The logic goes, “Target resources on places where the numbers are close,” and they are never close in Indiana. There is also a saying that even the Democrats in Indiana want to be Republicans.

While registering voters outside a grocery store, I had a young man who looked like Eminem pass me by and then come back as he left. I asked him if he had registered to vote and he said no. I asked him why and he said he was “scared.” This puzzled me, so I delved. He seemed willing to engage. “What are you scared of?” He responded, “I have never done it before… but I liked Hillary.” I did not expect that answer. He had never voted before but followed news enough to know that the Democratic primary had been a contentious process. I was not sure whether or not to ask why he had supported Hillary and talk about specific Obama policy distinctions, but that day I was there to register voters, not persuade. Trying to acknowledge his position, I assured him that voting is important, and he could go to the polls with friends and family. He filled out the voter-registration form.

Hoosiers

My Hoosier sensibilities run deep. I am not sure if what I think of as Hoosier sensibilities can be limited to people who claim the Hoosier label. For one, I was actually born in Louisville, Kentucky, spitting distance from the Ohio River, the Indiana/Kentucky border. It is even called Kentuckiana on local newscasts. I am a little bit bourbon, a a lot Derby, a little Indy 500. We sang both “On the Banks of the Wabash” and “My Old Kentucky Home” in my grade school choir. I love John Mellencamp and Bill Monroe. The distinction blurs when you think about the fundamental truth that culture is simultaneously local and universal.

Hoosiers “visit” folks. To “visit” means to take time to be with people that matter to you. This manifests in several ways. It can be seen in the connection with family. It is also present in a generosity of spirit that dictates that if someone needs something you pitch in and help out as you can. Sprinkle in a basketball obsession and that is the Hoosier way.

Being a Hoosier is definitely complicated by a discussion of politics, race, economics, and religion. Historically, Indiana has been a safe haven for the Ku Klux Klan. Both urban and rural issues exist from East Chicago to Evansville. Indiana has felt the devastation of the collapse of the industrial economy firsthand. Big farms with looming silos form its skyline throughout the state. The church you attend largely determines your friendships. Family roots run deep. Segregated neighborhoods struggle to embrace the changing complexion of our country.

In thinking about being a Hoosier, details and descriptions that draw lines that are too clear can cause problems. I am uncomfortable with generalizations that create one picture of any region or place. Any rural/urban, north/south, east/west distinctions are only as useful as they generously embrace the nuance that is our strength as a country — a unique, diverse, evolving democratic experiment.

The Yard Sale Evangelist

In October, I spent a day knocking on doors of “sporadic” Democratic voters in Clarksville, Indiana. These are people who have voted Democratic in the past, but haven’t voted in a while. I was trying to persuade people to vote for Barack Obama. On this sunny Saturday, I drove up to a home that was hosting a yard sale. In typical yard-sale fashion, there was a homemade white sign with black letters attached to a stick in the yard announcing the event. Tables that looked like they had been part of many a church dinner were strategically placed around the two-car garage that was behind the two-story red brick house.

It was about 1:30 p.m., so the early rush had passed, and, with the exception of a few lamps and clocks of various descriptions, the tables had been pretty much cleared. A pair of lime-green and orange upholstered chairs and a faux-oak entertainment center sat alongside the tables. An older woman rose from one of the lime-green chairs and asked if she could help me. I introduced myself and asked if I could speak to the person whose name was on my list. She looked at me with gracious yet suspicious charm and said she would get him. In retrospect, there was probably a knowing glint in her eye.

She walked to her kitchen door and gently yelled into the house. No one answered. I stood in the driveway looking at the lamps and remarking that it looked like they had had a good morning. She waited as the elderly man emerged from behind the garage. He slowly walked toward me.

I introduced myself and asked if Senator Obama would be receiving his vote in the coming election. He took a deep breath and looked at me as though he was looking through my soul. “You are participating in the demise of the country,” he said with a steely, yet somehow gentle, conviction. Tears welled in his eyes. His open heart inspired something in me that wanted to stay and talk with him, to hear what this seventy-two-year-old, former public school bus driver had to say.

He said he had voted for Eisenhower and that he knew when Lyndon Johnson and the Great Society came to power it would mean the end of the United States of America. He told me he prayed every day. He talked about how the ACLU was ruining this Christian nation, and how Barack Obama was part of a Muslim plot to take over this great land. He asked if I had read the Koran and encouraged me to read it and learn about the violent world Muslims want to create. I responded with a simple “yes” or “no” when he asked if I had read Revelations, or knew the story of Jesus and the moneychanger. I don’t think he really wanted to know my thoughts; I think he was mainly checking to see if I was listening.

After about twenty minutes, he got to the main point of his message. He had reached a crescendo of fear couched as faith, hatred he understood as love, and intolerance masquerading as patriotism. He asked me if I thought I was going to Heaven. I told him I believe in Heaven. I assured him that I thought I was going to Heaven. I said that when I meet up with Saint Peter, and my list of deeds is read, I think I will be given the green light. I assured him I try to live my life honestly, justly, and lovingly. I try to take care of my neighbor. I try to make amends when I have offended and forgive people who may hurt me.

He looked concerned. He asked if I had accepted Jesus Christ as my Lord and Savior. I then realized he was worried about the salvation of my soul and that my explanation of why I would wind up in Heaven would not suffice. He said there is but one way to the Kingdom of Heaven and that it is through Jesus Christ.

He asked if he could give me something. I said sure. He came back a few minutes later and handed me a little red New Testament, like the ones you find in hotel rooms. Before he handed it to me, he made me promise not to throw it away. I assured him I would not. He thanked me for listening and said he hoped I would read it. I said I thought we could agree that there needed to be more love in the world, and he said there would be because Jesus was coming. He thanked me again for my time. I said that he must have really wanted to talk with me because the University of Kentucky’s basketball team was on TV. He said talking with me was more important. He ended our conversation by saying he would pray for me. I thanked him.

As I drove away I wondered how did he come by his views? Would an inability to listen to and hear him be as intolerant as his words? In what ways was the passion that drove me to knock on strangers’ doors and ask for a vote any different from his desire to give a stranger scripture? Somehow I left there a little less sure of myself, believing that I needed to listen even more, to connect even more, to reach out even more.

The Clark County Democratic Party Pig Roast

In Clark County, Indiana, pig roasts are very important in the local political landscape. I was invited to the Clark County Democratic pig roast by the county Democratic Party chair, a family friend who had served with my father on the school board when I was in elementary school. This year, Clark County Democrats were serving fried chicken rather than roasting a pig, because pig was too expensive.

The county political machine showed up wearing buttons, buying raffle tickets, bidding on auction items, kissing babies, and talking with people. These people had been in the county prior to this election season. They had dealt with the bond issue to pay for the new county connector road. They had approved the zoning ordinance that allowed the triple-X theatre to expand next to the mega-church. They knew who-was-who and where the bodies were buried. As I sat eating chicken and baked beans, I knew that these were the folks who would be doing the work long after the votes had been tallied and the campaign office had gone. They possessed a marathon-like approach to community service, civic engagement, and political activism that had seen Indiana politically morph and change over the years.

I looked around the room, feeling simultaneously comfortable and queasy. I had left home. The county sheriff was the uncle of a good friend from high school. The mayor was a former neighbor. A woman I graduated from high school with was in charge of the county Board of Elections. People approached me asking me about where I was now and what I was doing. I found out about their families and how things were going in their worlds. I felt uneasy in the midst of connecting. For a moment, my very presence did not feel right.

Seeing people who made a long-term commitment to my community made me think about my choice to leave the community. Knowing the need that existed in my own backyard made my feelings about choosing to leave more complicated. Would the national campaign and the subsequent administration make good on the promises being made to win local votes? I was back in the middle of the people and issues I knew instead of in Washington, DC in which the distance between a policy and the people it impacts can seem so great as to make connecting the two impossible.

An Obama Rally

Barack Obama visited Indianapolis on a rainy Wednesday during the campaign. I made the trip from Jeffersonville to Indianapolis with Clifford, a retired machinist. We met at the Jeffersonville field office at 7:30 on the morning of the event. Years of working near loud machines had taken their toll on his hearing, so our conversation was a bit difficult. We talked about his wife of forty-five years and how they met, their children, and what they did during the weeklong power outage that the entire Louisville area had suffered as a result of hurricane-force winds earlier in the year.

Clifford had been involved in politics for a long time as a union leader and had taken his grandson to see Joe Biden when he came to Jeffersonville in September. A Kennedy-loving veteran, he felt strongly about the need to end the Iraq War. A two-hour drive did not stop us from making it to Indy to see Obama. My check-engine light did not stop us. A cold and rainy morning did not stop us. Unbelievable traffic around the Indiana State Fairgrounds did not stop us.

We arrived two hours early and already the line to get into the stadium where the rally would occur wrapped around the entire circumference of the state fairgrounds. Hoosiers were turning out in the rain for Obama. We walked in through security, surrendering our umbrellas, and made our way to the closest seats we could find. An army of volunteers made sure the line was moving and signed people up to volunteer with the campaign. The energy was electric. The rain did not stop the crowd from being fired up and ready to go. As people poured in, it was clear there would be thousands of cheering supporters. It was also reassuringly evident that security was a serious consideration as uniformed officers were strategically stationed throughout the crowd and above and around the stadium.

Music played, politicians spoke, CNN covered the event, and the anticipation built. A motorcade pulled up behind the risers in front of the crowd. The music stopped. The crowd erupted. Let me remind you again, this was Indiana, and we were not doing anything related to basketball, so the out-of-character nature of the enthusiasm cannot be underscored enough. Senator Evan Bayh ran onto the stage and fired up the crowd with a story about being a child and going to hear Lyndon Johnson, the last Democrat who Indiana had supported for president. He said he had brought his sons on this day, because he wanted them to be able to say the same thing when Barack Obama carried Indiana. The crowd erupted and Senator Obama took the stage. With an energy and a sincerity that I could feel from the bleachers, he greeted people around him on the platform. He started his remarks. He thanked Indiana for turning out that rainy morning and spoke about specific policy concerns that he knew worried everyone: the financial crisis, job loss, healthcare, Iraq — a daunting list, but one that did not seem insurmountable as he stated his approach to solving these problems. The crowd moved between listening and cheering, rapt attention and unbridled enthusiasm. After about forty-five minutes of talking straight to us about his vision and plan, Senator Obama concluded his remarks. He thanked us again and left the stage.

As I left the stadium with the other twenty thousand people, I knew I had witnessed something very special. I felt that my effort to support the campaign had been validated by a candidate who wanted to thoughtfully lead my country to be a better, more peaceful, and more just place. I left feeling that Senator Obama had a steady hand and a clear mind that would be able to address war, economic devastation, and environmental degradation.

Election Day

Election Day started at 4:00 a.m. I jumped in my car and headed to the field office. I turned on the Louisville NPR affiliate. Nobel Laureate Toni Morrison was on All Things Considered, talking about her new novel, A Mercy. A Mercy details the story of slavery in seventeenth-century America through the eyes of black, white, and Native American people. My route wound alongside the Ohio River, the same river which framed points along the underground railroad. As she talked about reluctantly coming to write about the topic of slavery, I could not help but cry. I wept for my country’s brutal history. I wept for the young girl in Mercy who knew the atrocities of that time. I wept in the knowledge that violence and injustice continue. Most of all, I wept because history and future seemed to be converging that day. I felt like we were on the verge of forever changing our fundamental definitions of power and race, and perhaps ushering in a country better than we had ever known. Driving along the same road that I had traveled to high school, to my job at a local pizza parlor, and to my church as a child, I felt something changing.

I arrived at the field office prepared to help organize the legions of volunteers who would be working at polls and others who would be making sure people voted later that day. We would first make sure all the precincts in the county were covered by trained poll watchers who had been assigned to them. Poll watchers began arriving at 5:00 a.m. Following the opening of the polls at 6:00 a.m., with all the people in place, we turned our attention to the volunteers who would be knocking on doors reminding people to vote.

Energy built throughout the day as more than two hundred volunteers worked in the Clark County field office of the Obama/Biden Campaign. People brought food. People made phone calls. People drove voters to polls. A steady stream of people filled the office and the crowd grew as poll closing time drew near. It came and went. We began to make calls to people in Northern Indiana, where it was an hour earlier, and polls were still open. We made calls, and people gathered in a spirit of celebration. As the polls closed in Northern Indiana, I went home to watch the results over pizza with my parents. Though McCain won my county, we delivered twenty-three thousand votes for Obama. Obama won Indiana by twenty-five thousand votes. He could not have won Indiana without us. He could not have been President without states like Indiana.

The Inauguration

I left Indiana and arrived back arrived back home in DC ready to begin my next chapter. A pile of junk mail had been forced under my door, making it hard for me to enter as I balanced a cat carrier and keys. Not long after, I received an email invitation to apply to be a volunteer at the Obama Inauguration. I completed the application and was chosen from a pool of thousands to volunteer during the week of inaugural activities. The day before the inauguration was Martin Luther King Day, which is dedicated as a National Day of Service every year. This year, the official inauguration activities included service and I was chosen to make care packages for troops serving in Iraq and Afghanistan. Hundreds of us joined together to make eighty-five thousand care packages that day. I stood next to Michelle Obama and her daughters as we stuffed bags. They worked alongside the volunteers, moving from table to table fully participating in our efforts for hours. As a thank-you, we were given purple tickets to the inauguration.

The morning of the inauguration started early. In addition my ticket, I had received two tickets for friends who were visiting from Texas. We walked to the Metro from my apartment. The bitter cold did not diminish our enthusiasm. Our breath crystallized in the scarves that protected our faces, but we were still fired up and ready to go. We were heavily layered. We proudly carried our purple tickets. My friends had made a sign that read, “Texans for Obama.” There was a serene energy on the train that morning. Despite the fact is was crowded almost beyond breath. People even smiled. We arrived at our stop and stepped out of the train into the sea of the crowd, security, and vendors.

It quickly became clear that no one knew what people with purple tickets were supposed to do. People acted like bumper cars in the pursuit of getting somewhere, though it wasn’t clear that anyone knew where to go. We were all just so happy to be there as we crashed and swerved.

After two hours swimming in the urban sea of Hope and Change, we found the purple ticket line. It wound around and around, through a tunnel for what seemed like two miles. We had to follow the tunnel in an effort to find the end of the line. People very nicely pointed out where we needed to be, while staking claim to their spots in line. We continued until we found the end of the line, about a quarter mile beyond the entrance to the tunnel.

The line was not moving. The clock was ticking. We waited. The line moved a few feet. We knew the inauguration would be beginning. We were caught in the tunnel. We stood in the tunnel. It was not as cold in the tunnel because we were shielded from the wind. People broke out in song: “We shall overcome.” We moved a few inches more. Minutes grew to hours.

The tunnel ended and we could see the gate to the purple section about a quarter mile in the distance. People were trying to merge into the line from the street. Confusion reigned, as we tried to figure out how to get into the purple section. We reached the gate and were told the purple section was closed. Like the moment when you realize there is no Santa Claus, I lost my breath. There was little time for disappointment or anger. We had to figure out a plan. The inauguration would start in fifteen minutes and we could not see a screen. Security made moving to a different section of the National Mall impossible. We walked several blocks and hopped a cab and watched the inauguration on the twenty-seven-inch television in my living room.

I felt uplifted by the being surrounded by millions of people united in something as big Hope and Change itself. Every mile on the road, knock on a door, phone call and conversation was worth it. I heard Barack Obama offer an inaugural address from the TV in my small apartment where I had made the decision to go home to Indiana and campaign. There was quiet and meaning to that context. I thought about the yard sale evangelical. I thought about the kids at IU. I thought about the people at home. I thought about my nieces. Our world was better because he was going to lead us.

About Katie

From Louisville. Live in Atlanta. Curious by nature. Researcher by education. Writer by practice. Grateful heart by desire.

Buy the Book!

The Stage Is On Fire, a memoir about hope and change, reasons for voyaging, and dreams burning down can be purchased on Amazon.