Katie Steedly’s first-person piece [The Unspeakable Gift] is a riveting retelling of her participation in a National Institutes of Health study that aided her quest to come to grips with her life of living with a rare genetic disorder. Her writing is superb.

In recognition of receiving the Dateline Award for the Washingtonian Magazine essay, The Unspeakable Gift.

Enter your email here to receive Weekly Wide-Awake

Understanding Equanimity

One of my favorite yoga teachers uses equanimity to describe warrior pose.

In yoga, warrior pose is a standing posture rooted in presence. I love warrior. I feel powerful in warrior. In warrior, my soft stare fixes my focus. I ease into a powerful bend that allows my legs and core energy to hold my body and my toes to grasp the mat beneath me. I know what it means to be sure-footed in warrior. When I fall, I get back up. My arms flex with strength and grace. I sometimes break yoga rules and look around the room when I do warrior. The overwhelming power of the gaze, the breath, the calm, the beauty, and the silence overtakes the space when we relax into warriortogether. There is a fierce softness in warrior that is part dance and part conversation. It is the physical manifestation of true balance.

Equanimity can be defined as mental calmness, composure, and evenness of temper, especially in difficult situations. We can also understand equanimity as when we are moved by injustice, motivated to do something to improve the world, and do not allow our inner serenity to be shaken. It is not about indifference. It is about maintaining a balanced heart that feels pleasure and pain, remains neutral in the conflict, and is present in trying moments. In Buddhism, equanimity is considered one of the four sublime states — upekkha. Edward Hoagland reflects, “There often seems to be a playfulness to wise people, as if their equanimity has as its source this playfulness or the playfulness flows from the equanimity; and they can persuade other people who are in a state of agitation to calm down and manage a smile.” Do you know those people? Jonathan Lockwood Huie affirms equanimity, saying, “I choose to respond to life’s provocations, not with anger, resentment, or regret, but with equanimity and a focus on positive action.”

A classic story clearly illustrates equanimity. A man walks to the edge of a cliff and leans over the edge to take in his surroundings. He falls off. As he is falling, he notices a vine. He grabs onto the vine to stop his fall. While holding on, he looks down toward where he is falling. He sees hungry tigers. He then notices a fresh red strawberry growing on the vine he is holding. Just as the vine breaks, the man picks the strawberry and eats it, fully tasting its flavor, while he falls to his certain death.

We all experience cliffs in our lives. Times when we feel like are falling to certain death. Times when things feel toxic, lethal, deadly, or overwhelming. Times when we feel like we are about to be (or are currently being) eaten by tigers. At these times, how do we quiet our mind? How do we move away from the cliffs? How do we stop the falling and the tigers? How do we taste the strawberries that sit in plain view? Can we be so present to life, sowide-awake, that cliffs and tigers are greeted with peace and even gratitude?

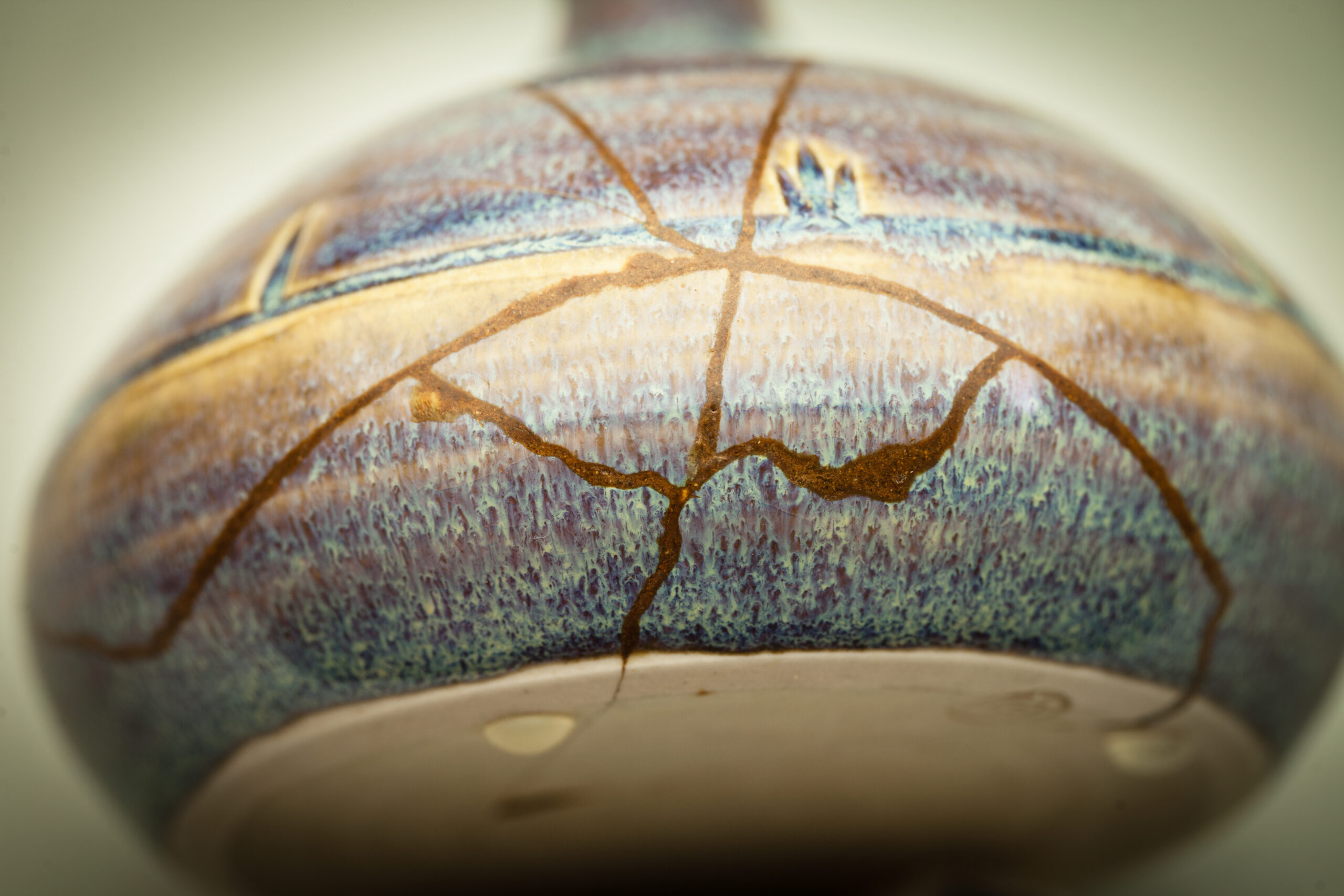

Rumi’s thoughts provide insight into the problem with equanimity. He explains, “Your hand opens and closes, opens and closes. If it were always a fist or always stretched open, you would be paralyzed. Your deepest presence is in every small contracting and expanding, the two as beautifully balanced and coordinated as birds’ wings.” Equanimity is the fluid opening and closing of the hand. Equanimity is the decision to be aware, engaged, focused, and vigilant while being open, soft, flexible, and kind. Equanimity is the small contracting and expanding that we commit to muscle memory when we forgive, when we say thank you, when we spend time with children, when wedance and sing. The deep presence of which Rumi writes is born of balance, and balance must be practiced and treasured amidst the flow of life.

About Katie

From Louisville. Live in Atlanta. Curious by nature. Researcher by education. Writer by practice. Grateful heart by desire.

Buy the Book!

The Stage Is On Fire, a memoir about hope and change, reasons for voyaging, and dreams burning down can be purchased on Amazon.